Reasons for homemade cake, mangonada, and appetite adornment

Emiko Davies selects her top Substack reads

This week’s digest was curated by Japanese-Australian cookbook author , who writes on Substack and is the author of six cookbooks. The latest, Gohan: Everyday Japanese Cooking, came out in October 2023 and won Fortnum & Mason’s Cookery Book of the Year Award. She has lived in Tuscany for the past 20 years. Some of her most popular posts include “You look so much better!” On nourishment and unwanted comments about your body,” “Antifascist pasta, a recipe and a story of resistance,” and “A love letter to rice.” If you enjoy Emiko’s edition today, be sure to subscribe to her Substack.

What I love most about the Substack newsletters that pop into my inbox every day is the sheer variety of writing that I am exposed to now. As a food writer, I lean heavily towards other food writers and, while I am interested in recipes of course, I also crave more than simply ideas for dinner. I love how personal some of these are—like reading someone’s letters, or diary entries—or how informative others are, how some really hit a nail on the head for me or make me think for days. Some are just a beautiful snapshot into someone else’s point of view, and that’s all you need.

Food writing need not only be just about recipes, because those of us who are writing about the food are also complex human beings, and writing out a recipe is only a tiny function, just the tip of the iceberg, of what food writing can be. Food can be complicated—feeding other people or ourselves is fraught with all kinds of emotional and cultural issues—but it is also a source of immense joy, capable of creating core memories or jolting you into old ones or taking you to places you have never even dreamed of going.

What a delight to be able to share some of the things I’ve enjoyed reading on Substack lately. It is not a coincidence that I have selected writers from diverse backgrounds and of diverse ages (two of them are in their 70s and 80s) or that they are all women—I hope you enjoy hearing their voices, as I do too.

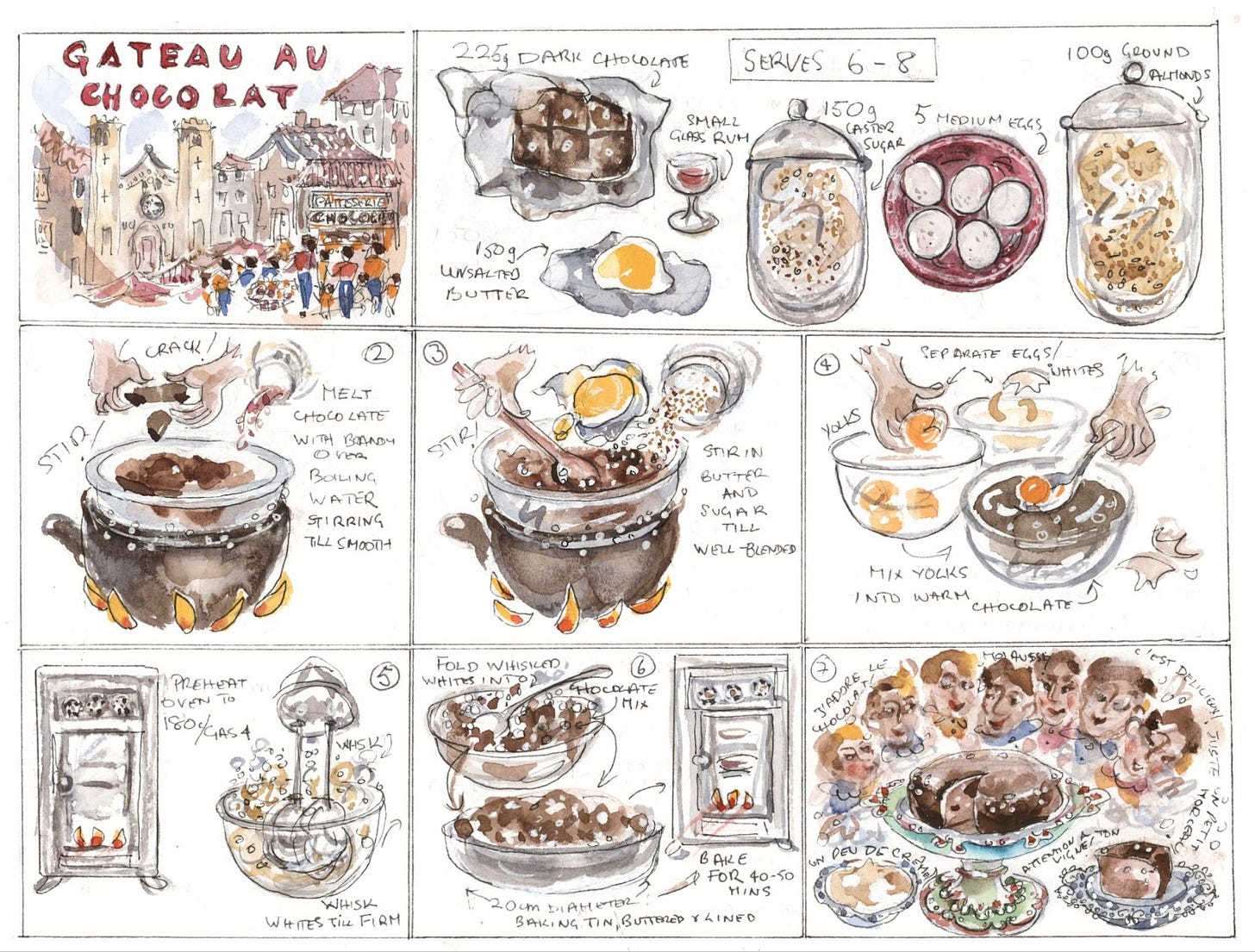

“Elisabeth Luard’s whimsical watercolours of recipes, travels, and ingredients that accompany her stories get me every time. Born in 1942 in London, the accomplished broadcaster, journalist, and author (15 cookbooks, four memoirs, and two novels) turns to Substack to share her illustrations (she trained and worked as a botanical artist in the ’70s through the ’90s), which in her words is a ‘cartoon cookbook.’ Whatever it is, it is a joy.”

Reasons for homemade cake

—

inShop-bought is all very well for les desserts, but homemade cake is right and proper for tea-time, preferably taken in a rose-arbour in the garden, whether yours or borrowed or municipal, it’s the thought that counts. It’s not even the scent and sight and taste of it (though sweetness speaks of summer to northerners in winter), it’s the preparation—the labour that could otherwise be used in more profitable ways, the serious thought that goes into the ingredients and choice of flavourings, the time it takes to beat, mix and bake what is not essential but is, in essence, for pleasure.

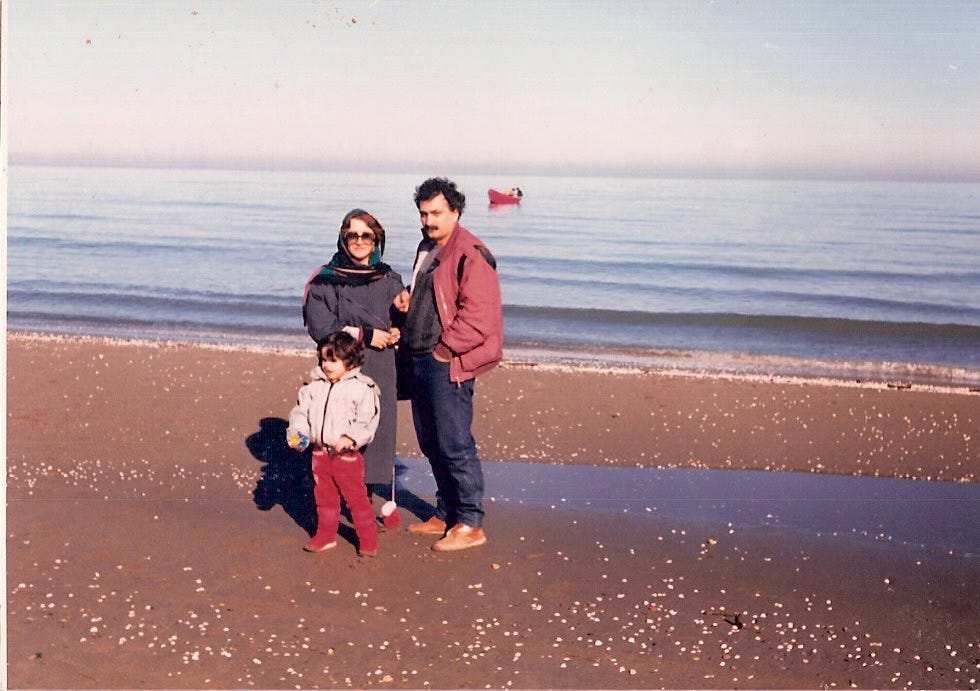

“Saghar Setareh, an Iranian woman living in Rome, is one of those food writers whose writing is never just about food but about so much more. I’m thrilled that she has started writing on Substack so I can read things like this story about her special connection to cats as pets, imaginary and real, while growing up in Iran. Immensely talented, whether it be in design, photography, or writing, she is incredibly honest in whatever it is she creates.”

Making amends to a ginger cat

—

inI was born in Tehran right in the middle of the Iran-Iraq war, during one of those many nights when missiles rained over the city like fireworks. About 4 years later, before the war was over, my parents went through a dramatically painful, but not quite successful, separation.

My mother and I briefly moved to my paternal grandparents’ house, as our house (whose windows had been shattered by other missiles and were held together by duct tape) was forlorn, because my father had a new family now.

I don’t have many memories from that period, except 2. One, that I discovered, or perhaps comprehended, “salad”: tomatoes and cucumbers and lettuce. I distinctly remember distinguishing every single vegetable and realizing that, when put together, it’s called a salad.

The second one is about, not so much of an imaginary friend, but an imaginary pet. A black kitten by the name of Sor O Mor O Gonde, which in Farsi is something ridiculous and a bit crass to say “big and healthy.” I must have heard the word from the adults and found the sound amusing, despite having no idea what it meant. That house, which had a garden like many houses back then, was said to be full of cats and kittens once, not as something endearing but more as a sign of lack of care.

“Nic Miller cleverly weaves history, memories, cookbooks, literature, art, and other references into her deep dives into food topics, be it mangoes or vinegar or trifle. She has a wealth of knowledge, but the way she shares it is in such an easy-to-absorb way (and with plenty of links) that you will no doubt end up going down your own rabbit hole once you start reading.”

Mangonada

—

inBefore I started researching a mango-related food column, I thought my knowledge base was pretty solid. It wasn’t, and, as usual, I ended up delving into all manner of mango-related stories…

A taster: Antique manuals about gardening in India. Probodh Chundra De’s A Treatise on Mango. Regional names for mango stones. A Burmese tale tells of a gardener who gave Buddha the gift of a mango whose stone was entrusted to his servant Ananda to ‘plant in a place which is prepared to receive it’. Arrows soaked in mango blossom oil to be shot into the hearts of gods and humans. Indian farmers uniting mango trees in marriage. The Chinese Mango Cult. Colonialism. Globalism. Localism. The mango…. A journey from Assam in India to… everywhere….

“Born and raised in Canada to parents from Japan and Hong Kong, Kana Chan now lives in rural Japan in Kamikatsu (a tiny village with a reputation for zero waste), learning to do things with her hands. This quiet newsletter is one of the things that often stops me in my tracks like a gentle and nostalgic memory, making me wistful for the rhythms of the timeless Japanese countryside that she writes about: learning the rice harvest, foraging, life in a kominka, an old Japanese home.”

A hidden cafe in the mountains

—

inStepping into Ishimoto-san’s cafe, Cafe Ikumi, is stepping into a bygone era. Relics of the Showa era (1950s-1970s) transport me to a place I’ve never been. The Showa era was a period of Japan characterized by rapid change and economic growth. Japanese people turned their gaze towards America and there was a dramatic change in fashion, culture, and music.

I had a glimpse of this time seeing the stuff my late grandma collected. She also owned a karaoke or snakku snack bar, which you can say is a kind of pub. Her shop was swirling with mystery, since it was off-limits for us as kids when it was open at night. In the morning we could visit, only to see remnants of the night before—tables yet to be cleaned, dishes that needed to be washed, an ashtray with the butts of cigarettes. The decor in the shop felt dark, dated, and retro. I don’t remember so much—only the feeling that this was a place that must have come alive during the night and in the morning that glow faded.

“Katie Okamoto is a Japanese-Spanish-American food and culture writer, journalist, and editor based in L.A., and I will basically read anything she writes about, whether it is Ricola in the Alps, mochi in a waffle iron, pillowcases full of Halloween candy, or socks adorned with bread. She has a refreshing point of view and a way of discussing everyday things that leaves me thinking about them long after reading.”

Appetite adornment

—

inI think there is a way in which putting a picture of toast on your body can feel safer than eating it. Most of the time, shopping for images of food to adorn our bodies is pure fun, self-expression, and I think sometimes that’s what it is. There’s nothing wrong with that! Probably that’s what it is for you, if you’ve bought any of these pretty things. But for myself, I am curious—even suspicious—when food shows up with abandon in aesthetics while eating food remains fraught. I am suspicious of my old desire to sate an appetite through fake food, rather than to look for what the appetite wants to tell me about my own body, my own safety, and my own freedom.

“Syrian-Lebanese chef, author, and culinary educator Anissa Helou is known for her cookbooks on Mediterranean and Lebanese cooking and currently divides her time between London and Sicily. Now in her 70s, she has been called the ‘queen of Lebanese cooking’ and one of the ‘100 most powerful Arab women,’ and her newsletter is a little glimpse into her kitchen, her travels, and the women who inspire her.”

A kibbeh mortar and pestle

—

inLong ago, before the food processor became a common gadget in most Lebanese kitchens, cooks used a mortar and pestle to pulverise ingredients. Most home cooks had two: one small and wooden to pound garlic and another large and carved out of stone for meat, especially meat for kibbeh (a seasoned mixture of minced meat and burghul, for those who still don’t know about kibbeh). My mother kept her garlic mortar and pestle in her spice cabinet whilst the heavy stone one was pushed to one corner, ready to be dragged to the middle of the kitchen whenever she and my grandmother were ready to make kibbeh. On that day, they placed two low wooden stools on either side of the mortar to take turns pounding the meat—it took a very long time beating on the chunks of meat to pulverise them into a pink, silky paste.

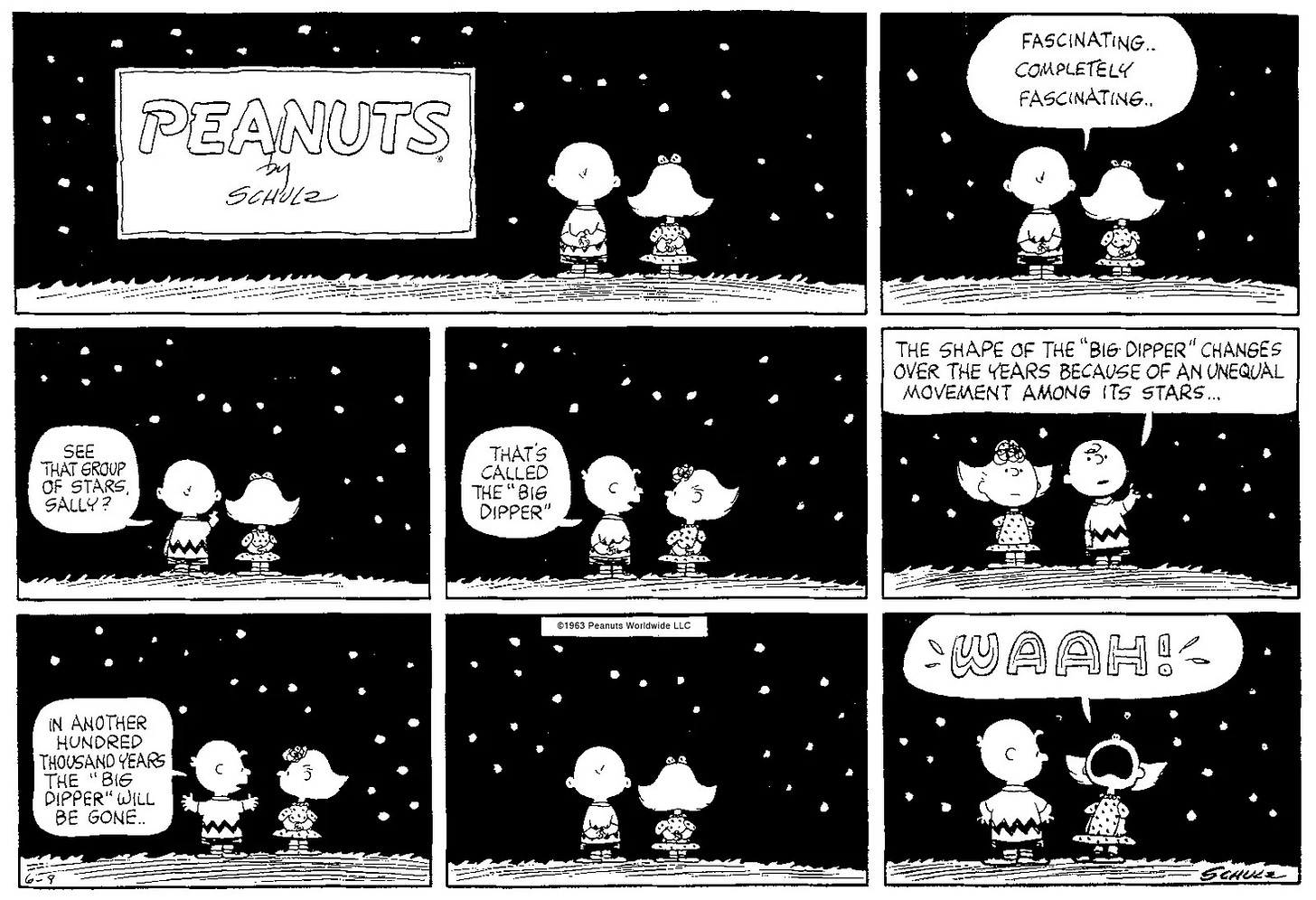

“The Kitchen Shrink is a weekly culinary advice column by chef and writer Tamar Adler and it is genius. From cooking fish on the grill to suggesting what to do with okara or how to eat lettuce with a sore tooth, there seems to be no question that Tamar cannot answer with depth, humour, recipe links—and an accompanying Peanuts cartoon.”

The inquest of involuntarily wilting

—

ofEven lettuce that is hanging by its nails from the fugacious plank can be made everlasting, if allotted the butter and salt and heat endurance demands.

Dear cook, acknowledge that your lettuce is both ephemeral and durable. Treat it lightly, or treat it firmly; be minimal, or buffet it with butter and demand its surrender in a Vitamix. Try hard, then let it go, and go along with it. Can it be both there and gone? Can it be anything but?

“Apoorva Sripathi writes broadly about culture and food from Chennai, India — covering recipes and thoughtful, personal essays. I first came across her work through a piece she wrote for on the pleasure and politics of eating mangoes, which is also worth diving into too, to get a sense of how she can transport you through words, while weaving memories, history and food politics deftly together.”

This writing life

—

inI’m standing inside the bus and holding onto a vertical railing. I turn around and everything is suddenly grey and lifeless, pithy and pale. I no longer have the purse and instead I’m holding an ice cream cone that’s dripping down to my fingers. I look down and I’m sitting on a pavement while someone I know is on my scooter eating a choco ice. We’re laughing about something and to our right are stacks of plastic crates with bags of milk (Aavin, Heritage, Aarokya). We finish our ice creams and take the scooter back home. The red purse has disappeared along with my memories of it.

Inspired by the writers featured in Substack Reads? Writing on your own Substack is just a few clicks away

Substack Reads is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, and audio from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and this week’s edition was curated by Emiko Davies, who writes Notes from Emiko’s Kitchen on Substack. Substack Reads is edited and produced from Substack’s U.K. outpost by .

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.