The history of Italy's partisans through food

Part I: The role of food in the fight against Fascism

Edited 8/2/2024 to remove the paywall to make this piece of history accessible to all!

There is only one way to share all the things I’ve learned recently from reading the fascinating history of Italian food during the 1920s-1940s, Partigiani a Tavola: Storie di Cibo resistente e ricette di libertà (“Partisans at the Table: Stories of food of the resistance and recipes of freedom”) by Elisabetta Salvini and Lorena Carrara, and that is through a multiple part post that I hope you’ll find as interesting as I do — and, of course, pasta.

I couldn’t put this book down. Full of first hand testimonials, in particular of women and young people (those that don’t often get their voices heard in history), it tells the story of Italy’s recent past, in particular the two decades of Fascism under the rule of Mussolini and then the two disastrous years between 1943 and 1945 when a tired, starving and defeated Italy switched sides. But more than anything, it is a story of the everyday people — teenagers, mothers, young women, farmers, who resisted and fought for freedom with food, grain by grain, often giving their lives.

I think anyone who loves Italy and Italian food really should know more about this part of Italy’s history. I couldn’t help but keep reading out passages to my husband, to tear up, to actually cry, through most of this book. There are a few parts I wanted to share — next week, in Part 2, I will share the story of the Cervi brothers and the recipe for their “antifascist pasta”, which is just one of many stories of ordinary people who became extraordinary heroes through food.

But first, a little brush up on Italian history.

Personally, I had to revisit my high school history of Mussolini and the fall of Fascism in Italy, which I thought I remembered well — but in Italy, obviously, everyone knows what you mean when you say il venticinque luglio, the 25th of July or the 8th of September. So if you feel like going down a rabbit hole before next week’s post comes out (just in time for the 25th of July), this very brief background (and some wikipedia links) can help put things into context.

Italy was under Mussolini’s fascist regime from 1922-1925 when he was Prime Minister, then from 1925-1943 as a fascist dictator. Italy entered the Second World War — quite unprepared — on June 10, 1940, when Mussolini enacted the Pact of Steel with Hitler, declaring war against France and England. But by 1943 Italy was facing defeat and the night between the 24th and 25th of July, 1943, Mussolini was finally deposed and arrested — and Italians celebrated, believing it to signal the end of the war. It didn’t last for long, though. On the 8th of September, Pietro Badoglio (the new head of government) read out a speech declaring that Italy was now joining sides with the Allies.

It was a disaster. The confusing message (many believed the war was over, here is an excerpt from The Guardian report on 9 September 1943 from Italy) meant the Italian Army disbanded, and within a few weeks over 600,000 soldiers were caught by Germans and sent to prisoner of war camps. Others (about half of all Italian soldiers), put down their weapons and went home. Hitler was a step ahead, having already predicted that Italy would switch sides and had his army ready to unleash fury on the traitors — they doubled down on acts of obscene violence, cruelty, massacres and torture not only towards partisans but to regular civilians, women and even children. The remaining Italians willing to fight either joined the Fascists or the Resistance — alongside independent fighters, partisans and anti-fascist parties fighting for democracy. So the situation was dire; Italians found themselves in the middle of both a world war and a civil war between September 1943 and the end of April, 1945, and what little food had been around at the start of this period grew even scarcer.

Food rationing

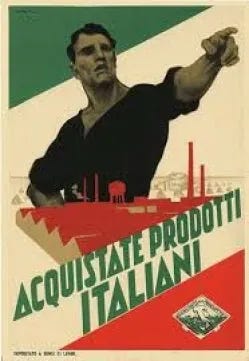

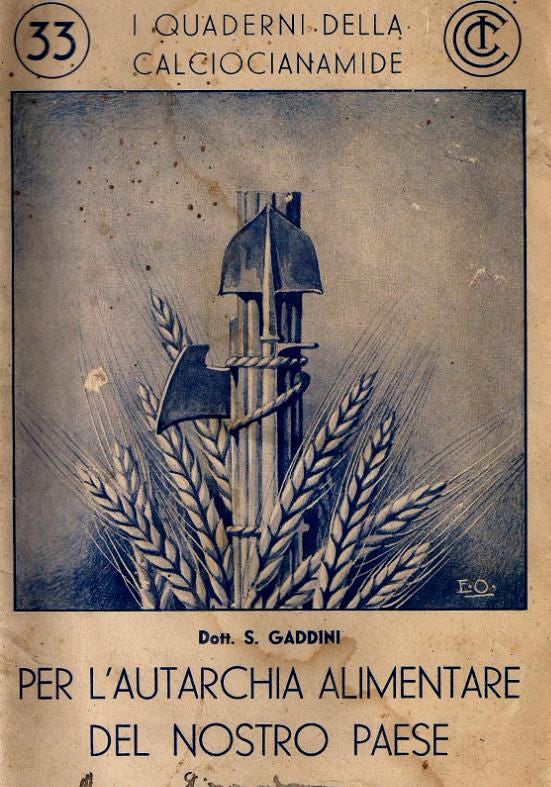

Food already becomes scarce in the 1930s. Cookbooks like Lidia Morelli’s (aka “Donna Clara”) Le massaie contro le sanzioni (published in a timely manner on 18 November 1935), taught Italian women how to make soup from vegetable peels and coffee from the toasted seeds of grapes, along with Fascist propaganda such as the merits of rice (more on this soon) and not using ingredients that come from abroad (interestingly in the list — yes there is a list — you’ll find things like Scottish whisky, Marmite, currants, English mustard, caviar, Spanish anchovies, Swiss chocolate and more).

In 1936, another cookbook, La Cucina Italiana della Resistenza (not that Resistance but more a reference to an economical resistance), the full influence of Mussolini’s propaganda on everyday housewives carefully chosen ingredients and meals to cook for their families can be felt: it is a book encouraging national self-sufficiency and zero kilometre cooking by refusing foreign ingredients and learning how to cook with what is only Italian — just like Morelli’s book above, the timing of the book is not a coincidence, as Italy was subjected to economic sanctions by the League of Nations when it invaded Ethiopia in October 1935. So — coffee (“fa male”, it’s bad for you anyway) should be replaced with chicory (or grape seeds or even acorns), black tea with hibiscus tea, cotton with fibres from the broom plant. Chestnuts appear in more dishes than meat.

When Italy entered the war, food was in short supply. There was already a special ration card (tessera annonaria) in place from January 1940 that limited the amount of coffee one could buy. But soon, sugar was added to the list (500 grams per person per month; this may sound like a lot but remember that sugar was an important preservative, in particular for fruit jams and biscuits — considering you often need equal weight of fruit to sugar, this is perhaps enough to make 2 small jars of jam). After six months, the list of items rationed included soap, olive oil, lard, lardo, flour, pasta and rice.

By October 1941, bread was on the list too (150 grams per head a day) and butter (which is, as described in Partigiani a Tavola, “guarded like a precious object to barter with the even more impossible to find salt”). Mussolini called on families to raise their own poultry for eggs and do their part for the country at war. Cities were of course far worse off than the countryside but in some cases “orti di guerra” (war gardens) popped up in city piazzas (Piazza Castello and elegant Piazza San Carlo with its ancient cafes in Torino for example), for growing grain and potatoes. People had to live with what they could find and obtain with their ration card (after lining up for hours — one account remembers her mother getting up at 3am to wait in line) and often there was nothing, rationed or not, to find.

Meat was rationed to 100 grams per person per week and was no longer available even on trattoria menus except for certain days of the week (and you had to be prepared to pay astronomical prices to eat at a trattoria, only very few could afford this luxury). If you didn’t have access to it on your ration card, you were given blood instead (a cheap and important source of iron and protein), which — according to the testimony of Giuliana Bornstein in La Resistenza Rimossa — was sold in blocks, coagulated. You could cook it like a steak.

Bistecca and roast beef eventually disappear of course, especially in the cities. But you could sometimes find a bit of salame, prosciutto or other homemade pork products, conserves and eggs in the countryside if you were lucky. Pasta too was hard to find (you will hear more about this in Part 2).

Food as Resistance

In the years leading up to, but especially during, the war, food played an important role in everything from boosting or crushing morale, as a form of blackmail or reward (Italians were encouraged to turn in partisans to the Fascists, in return for five kilograms of salt), torture and intimidation (German soldiers forced suspected partisans to drink castor oil, causing the victims to vomit the precious little contents of their stomachs, and there are stories of stanga caplet, cappelletti in brodo for Sunday lunches that were ruined, smashed by Germans with long wooden batons).

But food is also an important form of comfort and healing. Food is so much more than just filling up empty stomachs, it is used to barter on the black market, it saves people’s lives, gives people hope. And this is of course where hundreds of thousands of women — being the cooks in the house — became silently involved in the war too. Many were the women who prepared bread and preserved milk and meat to send up to the harsh Alps where young partisans, fighting for liberation, had no other access to food. “Se c’è ne, mangia per tre” was the partisan rule — If it’s there, eat for three — because you never know when you’ll get to eat next. It’s an aspect of partisan life reflected also in Italo Calvino’s Il Sentiero dei Nidi di Ragno (The path to the Spiders’ Nests), the author’s first novel, published in 1947, where young partisans guzzle down boiled chestnuts.

Food is used as a form of resistance. Farmers, like the Cervi family, who you’ll hear more about in Part 2, would keep a precious portions of meat, grain and milk that Italian farmers were forced to give up to German troops to send back to their country, at one point even faking an epidemic to keep their cows and share with other partisan families. But as described in Partigiani a Tavola:

“Each grain of wheat, each drop of milk preserved becomes “food of the resistance” which serves to feed the family, draft dodgers, partisans, prisoners and disbanded soldiers. Through food, Italians decide which side they are on. Enrolling in the army of the newly formed [fascist] Repubblica of Salò means having the security of a salary and warm, relatively abundant meals. On the other hand, refusing the call to arms and taking the mountain trail [with partisans] guaranteed certain hunger.

Hunger

Hunger causes women (in their role as housekeeper) to invent dishes and find food any way they can. In an effort to make life feel “normal”, and familiar, women learn how to make oil from walnuts (as olive oil is impossible to find), coffee from grape seeds, or even acorns, to make soap at home and transform parachutes into shirts and bicycle tyres into the soles of shoes (more of this is described in Miriam Mafai’s Pane Nero: Donne e Vita Quotidiana nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale).

Italy was starved during the war. By 1944 there was no food to be found, rationed or not. An testimonal from Rome from Bandiera rossa e borsa nera, recounts, “Here we die of starvation. There is nothing to be found: no meat, no chicken, no vegetables. The Germans are starving the city.”

A testimony from Fiorenza Frizziero Scandola from La guerra alla guerra, describes one meal after a bombing blows off the lid of the family’s dried maize, which they then grind into polenta before cooking. Then, sitting down to the simple meal by candlelight (because there was no electricity), her sister notices something strange in the polenta, “It glitters!” There was glass in it. Her father urges her to throw it away, worried it will make her sick, but her sister eats it anyway because hunger was scarier.

And this piece, the testimony of Bruna Tallura in Scenari di guerra, parole di donne, describes hunger during a winter meal during the war:

“You take a crumb from your ration of bread, curbing the desire to eat it all in one go. This is the first act. The first gesture is instinctive. Then the “focaccia” of cabbage leaves arrives pompously at the table and hunger, that real hunger, makes what you would normally politely refuse, seem like an excellent dish. You devour your ration of cabbage, skimping on the bread for fear that it won’t be enough and so you study various geometric possibilities to calculate the number of bites that you can obtain with the bread that is left… You get to the last bite and you clean your plate carefully with it until it shines. The meal is finished in a few minutes. Another pause, full of hope for a surprise. Now the oranges enter the scene. Cabbages and oranges. First you peel them, maybe with a knife and fork, leaving the peel on the plate, then, almost distractedly, you eat the peel too because you’re hungry. Dinner is finished.”

The war against pasta

Next week’s Part 2 will cover the war against pasta (as it was not patriotic -!!) as well as the Cervi family’s “antifascist pasta” to celebrate the fall of Mussolini.

Let me know if there are more aspects of this story that you want me to write about or have questions about, I’ll add them in the next post.

Partigiani a Tavola, by Lorena Carrara and Elisabetta Salvini, Fausto Lupetti Editore, 2015, with a preface by the great songwriter and singer, Vinicio Capossela.

This is all fascinating and I’m looking forward to part two.

When I arrived as a student in Florence in the mid 1980s I was amazed how close the war still was. In the US it seemed like ancient history, but in Florence it felt close and woven into the fabric of the city. My landlady told us stories of having to make her way across the city to find a bit of bread, dodging dangers and knowing her baby son was at home.

My Italian teacher assigned me a book that year, L’Agnese Va a Morire--it was a heartbreaking story of an older woman who joins the resistance. The writer, Renata Viganò had also been a member of the resistance.

Learning more about the food and how it evolved through these times really brings it into focus and makes it more real, thank you.

Very interesting. I have heard a few stories from my in-laws family. one part was in the mountains of Marche where the maternal nonno was veterinario, in Sarnano. He often was paid in food, so they did not starve so much - but most of their extended families started to flock there, plus children were sent to them, away from dangerous cities, which made feeding this crowd a real headache. On my father-in-law side, situation was much more dire, since his father (and 2 of his sisters) had died early of tuberculosis and they were shunned by the rest of their coastal village as unsafe. Hunger was real but, thank goodness, there was the sea, which delivered always a little something.