Thank you for being here! I recently attended a whirlwind 2 day conference on Women in Food hosted by Corriere della Sera, one of Italy’s main newspapers. It was moving, exhilarating, empowering and inspiring, if anything because of being simply in the presence of sixty women who count food as their major passion, their salvation, their identity or their livelihood (see some highlights here on Instagram).

I was asked to give a 15 minute lesson on how to write about food and when the editors asked me to pick one word to describe my lesson, I responded without even thinking, “storytelling.” The video of my talk is only available to Corriere della Sera subscribers, but I thought it would be fun to let you listen to it … as a podcast! A first for me, so you get to hear it first too! Let me know what you think about this format. Below you’ll find it all transcribed too.

I grew up moving between Australia and China, where I lived for eight years as a child and adolescent. With my Japanese mother and Australian father, a diplomat, we traveled a lot. Ever since I was a child I've loved exploring new cultures and I've loved tasting my way through a new place to get to know it. This, I think, was the start of understanding how food can tell a story.

When I begin writing a cookbook, or even just one recipe, I start by thinking about how a dish has a story to tell. Without the story — the why, the what and the how behind a recipe — what is left? Stripping the recipe of its context to me doesn’t feel right, both as a writer and as a reader. I want to know why these ingredients are together, I want to hear the reasons behind the name, the history, the traditions behind the dish — is it eaten for a special day of the year, is it celebrated in a particular way, it a family recipe? What makes it a family recipe?

My 10 year old blog and very first cookbook, Florentine, both came about because I realised that there were no cookbooks or even food articles about Florentine cuisine in English, many of the stories behind the dishes were simply unknown at the time, not even Florentines talked about or knew them anymore.

Finding the food stories for my second cookbook Acquacotta, which is about the cuisine of the Maremma, was like searching for a needle in a haystack. The first thing I did when I moved to Porto Ercole on Monte Argentario in southern Tuscany was go to the bookshop in town and ask for a book of the local cuisine. I was hoping to find something on cucina maremmana, or if I was lucky, Monte Argentario. The shopkeeper handed me a book with the title, Cucina Italiana.

These recipes were so hard to track down, almost forgotten, and I wanted to document them in case anyone like me, who had fallen in love with this corner of land and sea, was curious about knowing these stories before they were completely lost – already, it's very hard to taste any of these dishes in restaurants on this part of the coast, which is dominated by the same menus that you'll probably find all along the 7,500 kilometers of Italy's coastline, things like fritto misto and pasta allo scoglio.

When it came to writing Tortellini at Midnight, I wanted to capture stories inspired by family recipes – interviewing the most elderly family members about their cherished food memories and how they remembered the recipes of the family members that I never had the chance to meet, before those stories were lost too. This book led me to both ends of Italy, to Turin and to Taranto, searching for recipes that connected the dots to the family tree, now in Tuscany.

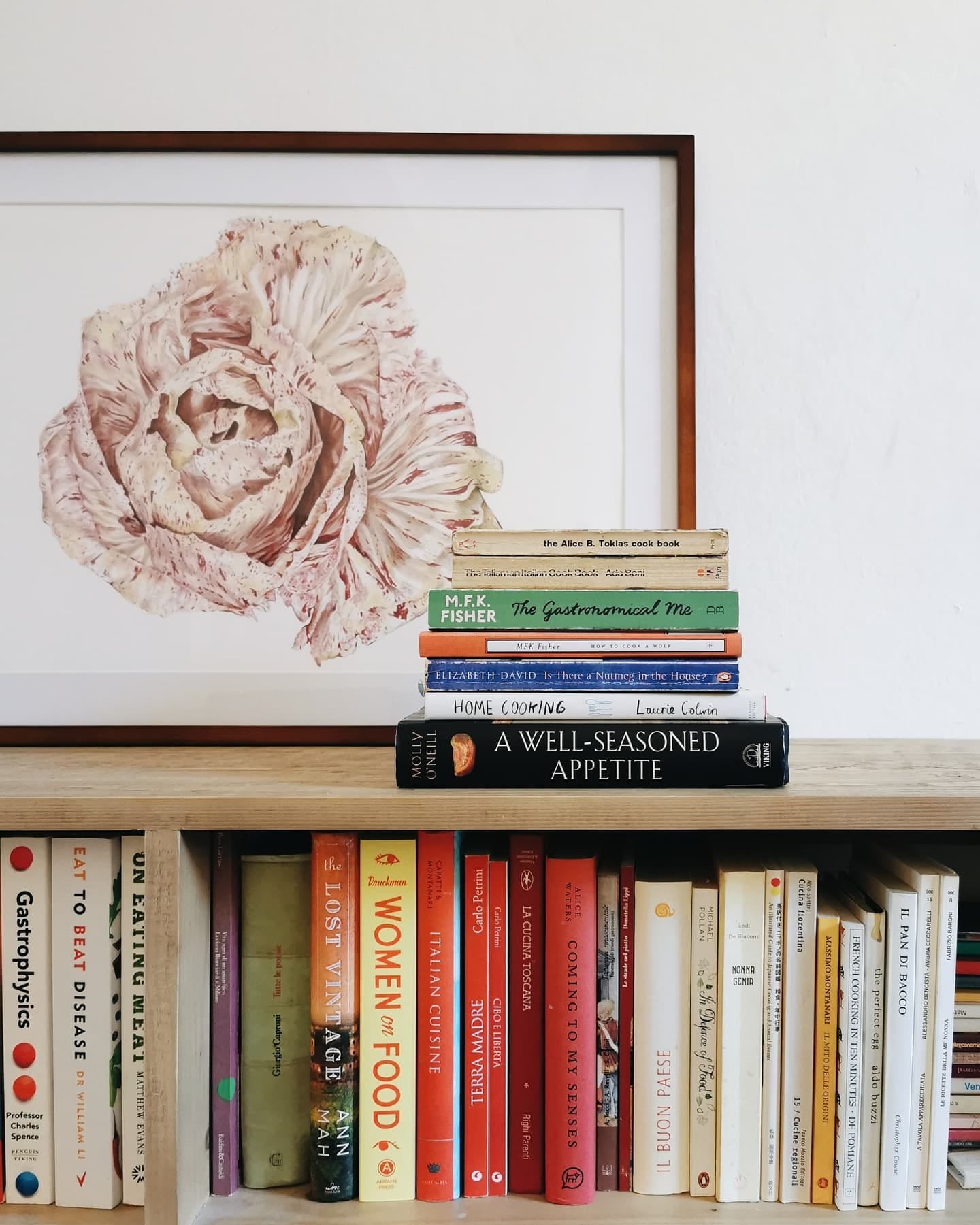

Writing and reading stories around food is something I have always enjoyed, even before becoming a food writer. I believe this started because I was a voracious reader as a child. Later, I read my mother's food magazines like novels. I even loved novels that had food as a central theme. Then I discovered some food writing that wasn't quite a cookbook but wasn't just a story, it combined both and was an autobiography on top of it. It was The Alice B Toklas Cookbook, which I found in a second hand book shop in Sydney. As I read about Alice and her partner author Gertrude Stein and what was on their table in wartime France, I was immediately hooked.

Some of the most influential and inspiring food writers for me I think have a way that turns a recipe into so much more than just a recipe. These are writers who have the ability to transport you while also giving you instructions on how to make soup or ideas for what to cook for dinner. I'm talking mostly about writers such as Elizabeth David, Patience Gray, MFK Fisher, Laurie Colwin. The first three women are writers who very often wrote about places they were traveling in or living in that are not their home country, like myself, while Laurie Colwin could write about anything in her fridge and find a story to tell.

Some contemporary writers whose work I love for their storytelling include Olia Hercules whose book, Summer Kitchens, about Ukrainian cuisine is one of my favourite cookbooks, and journalist Caroline Eden's Black Sea, which shows you how journalism and food writing can be intertwined so well. I also love Rachel Roddy's column at the Guardian. Much like Colwin she can write about anything that is happening at home, even the most mundane thing, and turn you immediately into the kitchen to go and make it.

Learning how to find a story to tell was something that came about for me I think because of a natural love of and curiosity for history.

Before being a food writer, I studied to become an art restorer. And I like to think that the way I research and piece back together a recipe is a bit like restoring an old book or an antique print: staying true to the original, trying to repair the broken or lost information and then tidying it all up.

A big part of doing that is simply through every possible avenue of research that I can find, who can I talk to about this recipe – is there a custodian of this recipe I can reach out to, chef, an elderly person, a family member, a butcher? What books can I read if it has already been written about, and also, where can I taste it? Is there a trattoria, a bar, a pastry shop, a market stall, someone's home, where I can try this recipe?

Just doing this research can give you already a story to tell – you can talk about the place where you tasted something, or the person who you learned the recipe from, whether from a book, virtually or in person. There was an old woman, Ilena Donati, who we met at a fruit stand on the Via Aurelia outside of Capalbio, while coming back from the beach. She was a cook for 40 years and recounted to me with great detail and precision the recipe for tortelli maremmani and many others – and I didn't even have a pencil and paper on me to write it all down. But I remembered her advice and I compared the recipes she told me about to the ones I'd tasted in the Maremma, at sagre and in trattorie. I compared it too, to things I'd read, like in Paolo Petroni's Il Grande Libro della Vera Cucina Toscana, as well as friends' family recipes, and I cooked them over and over again to get them right. Here is how I added Ilena's story to my book, Acquacotta:

“One extremely hot summer's day, while taking some friends out to visit nearby Capalbio, we spotted a roadside fruit and vegetable stall. Go there! was the unanimous cry from the back of the hot car. We were greeted with a small paradise: ice cold, lengthwise quarters of watermelon, bunches of fresh basil, baskets of purple and yellow plums, round and lavender-striped eggplants, fragrant rockmelon, traffic light-coloured peppers and cucumbers twisted in all manner of shapes. We filled a bag to the brim. After a bit of chit chat with the shopkeeper, Gianni, on what to do with serpent beans and whether he had a good recipe for acquacotta, he decided the best thing to do was to introduce us to his neighbour, Ilena Donati, an elderly but spritely woman, who had been, for most of her working life, a cook in Capalbio.

She was generous with her advice – let acquacotta cook piano, piano. That goes for cinghiale (wild boar) too. The farro soup is good cold with a drizzle of olive oil. And, my favourite, “buy yourself a big, black pan”. She meant a cast-iron one. “I can't tell you if these dishes will come out well with a non-stick pan. But in a cast-iron pan, they're wonderful.” she said. The recipe I have immortalised in my memory from that moment is her recipe for wild boar. Cinghiale. In pieces, with the bone, of course, as it's more flavourful. Don't marinate it, she said, referring to the common practise that everyone's nonna has always advocated of marinating game in red wine for 24 hours before cooking with it–to remove the “wildness” of the meat, as they say. It disguises the true flavour of the meat. Besides, the wild boars today aren't like the ones they once were. Lots of bay leaf. Lots of rosemary. Whole. A pinch of chilli. Not everyone likes it, but it's good. She said it in a way that means the chilli really belongs there. And brown the meat. Brown it really well. Add a splash of vinegar. When that evaporates, add “vino nero,” literally black wine, an old fashioned way of saying red wine. And then tomatoes, broken down with your hands–she gestures with her hands as if holding them above the pan and I'm imagining the feel of peeled tomatoes being squashed between my fingers “–and cook it, piano, piano.”

Some recipes are easier than others to research and some recipes are easier than others to tell stories about but one thing I think is important is to remember to give a place to the recipes that you think might be unpopular, that no one might make, but that have a story that are a vital piece of the puzzle.

I know that no one in Australia, for example, is going to make the panini al lampredotto from Florentine, because they live somewhere where it's virtually impossible to find lampredotto – I know, I went to every good butcher in Melbourne looking for it and it simply wasn't an option. Not only is it difficult to get the fourth stomach of a cow in a place where it's not usually eaten, but offal isn't high on many people's menus at home either anymore. But for me, this is the most Florentine recipe I can think of. The thing you can only get in Florence, that has a special link to the city, that tastes like the city, the top Florentine food experience. I knew I couldn't write a cookbook about Florence without having that recipe in it. I have heard of cookbook publishers not allowing recipes with ingredients that are hard to get. But I made this really clear when it was one of the ten recipes I included in my pitch when I proposed the book to my publishers.

In Tortellini at Midnight, there is a recipe for torta con i ciccioli, a sweet, dense cake made with lard and rendered pork fat in it. I know no one is going to bake this cake (they should though, it is delicious). It's too old fashioned and no one unfortunately seems to want to bake with lard anymore. But this recipe, a lost family recipe, was recounted to me by my husband's uncle as a special memory of his nonna [I talk about this recipe and the behind the scenes of it in this past letter here], and I cooked different cakes for him until we found something close. It became one of the must have, most treasured recipes for me in this book, not only for the emotional value but because it shows, for me, exactly why telling the story can be such a vital aspect in preserving a recipe. I'd like to finish with this excerpt from this recipe:

I was dropping in on Marco’s aunt and uncle, Franca and Riccardo a few years ago. We let ourselves in through the gate, attempting not to let Asia, the giant Maremma sheepdog, escape, and slipping into the house where, behind several piles of books, Riccardo was printing out a short story to share with me. It’s about cake; he thought I would like it.

It was a cake often made by Nonna Maria, a farmer’s daughter from the countryside near Pisa, and a baker. The cake pervades Riccardo’s memory like a ghost. He remembers the smell, the taste, the month of the year – she made it in November, a month of cold, short, rainy days, during a festive season when the fair would come to town. He remembers it as “una bomba” – of calories, that is. A very dense, short cake, heavy with eggs and lard (olive oil and butter were luxuries). It was eaten it around the fire, one piece devoured after another.

Riccardo had spent years searching for this recipe, based entirely on the memory of eating it when he was young. At first we thought it might be like a sort of Florentine schiacciata alla fiorentina, a fluffy, yeasted cake typical of Florence, made exclusively during the Carnival period in February (already that made raised my doubts), heady with the aromas of orange zest and vanilla and enriched with lard. I made it for him to try, but it was too fluffy, too perfumed, too dainty with its veil of powdered sugar and cocoa powder, to be the one.

“It’s more rustic,” Riccardo said.

“And more dense, much more dense,” Franca piped up.

They got married when they were 17 years old. They have been together for over sixty years and have three great-grandchildren. Even Franca remembers this cake. In fact, although it’s Riccardo’s memory, Franca is a great cook, and she knows cakes, so I listen to her recollection of it too and in particular to a detail that Riccardo doesn’t mention.

“There were ciccioli in it,” she assures me, speaking of savoury, crunchy, porky bits scattered throughout the cake.

Ciccioli are small, dry pieces of fatty pork, cooked slowly until dry and all the fat has melted out of them – this part is then drained for making lard. They are at times spiced or salted, but at their simplest, left plain and unseasoned. To the cake, they lend crunch. Similar to pork scratchings, they can be eaten as is as a rather addictive snack, but it’s more traditionally found sprinkled through polenta, bread or, in this case, cake.

I didn’t have to look very far for inspiration – Amongst the 790 entires, Pellegrino Artusi has a recipe in his nineteenth century cookbook for focaccia coi siccioli (ciccioli). And although he calls it a focaccia, it’s not a bread but actually a sweet, very dense, flat cake. It’s a country cake has that has a comforting, satisfying quality worthy of cherishing as a memory for a lifetime.