I recently was asked to present a Guest Lecture at Monash University in Prato, north of Florence, for an intensive course on sustainability in Tuscany. Phew, what a Pandora’s box of a topic! I decided to tackle the question how sustainable is Florentine food and hone in on Florence, and combine tourism, hospitality and Tuscan traditions into one talk. I really enjoyed researching this and talking about this with these keen students who also had the best questions for me at the end of the talk (I’ll reveal my favourite at the end) so thought I would share a condensed version here too as this is something I believe we should think more seriously about, at home as well as when we travel.

How sustainable is Florentine Food

Let me paint a picture of the situation in Florence. Florence is small and dense. It would take you not much longer than 30 minutes to walk across the entire width of the city, from Porta al Prato to Porta Santa Croce. Florence has about 380,000 residents, spread out in the suburbs also around the historical centre. But it is a tourist’s city, so in terms of visitors there are many more people in Florence on any given day. Officially Florence has 11-12 million visitors a year (this is calculated on those paying city tax and being registered through hotels etc), but unofficially, when you count day trippers and visitors who aren’t registered through hotels, I've read estimates of 24 million. That's almost the entire population of Australia passing through a space that is roughly 1/100 of Melbourne every year.

When the city was emptied of tourists during the hardest parts of the pandemic it became more obvious than ever that Florence is increasingly a city made for the service of tourists rather than residents, and you can see this in everything from the housing to the shops and restaurants to the parking and other practical services. To feed 11, (maybe 24) million visitors annually you need plenty of restaurants, bars and gelaterie.

You can't walk through the main streets of Florence without being confronted by an exhausting number of restaurants and bars — and something I've noticed increasingly, restaurants with windows full of carcasses and huge bistecche (steaks) on display.

Bistecca is the king of Florentine dishes on restaurant menus these days. But it is not the only thing you should try when you visit Florence. So why is bistecca the “must have” when also crostini di fegatini – chicken liver pate on crostini – are a classic in Tuscan cuisine, in fact, more of a “must”. Crostini di fegatini are present at every important get together, the start of a typical Tuscan meal as part of the antipasto. Bistecca however, is a rarer thing, to be had at special occasions to be shared with family, like a roast.

Or how about panini con lampredotto? I cannot think of a more Florentine thing to eat. You can only get these in Florence. It is the number one thing I tell people to try when they ask me what should they eat in Florence. Only the Florentines even eat this cut of meat – more on this soon. And eating a drippy, warm panino full of juicy lampredotto with some salsa verde and chilli sauce, on the side of the road at the van where it was made, is one of the most Florentine food experiences you can have. Yet the number of lampredotto food trucks isn't going up.

I do get it. Bistecca is more appealing than tripe or liver. A huge 4 finger-thick steak, grilled over charcoal stoves is impressive. But when you think about the number of restaurants not only serving these but displaying piles of them in their windows every night of the week in Florence, I shudder to think about how unsustainable this is.

Bistecca is traditionally a special occasion meal. In the Renaissance, the Medici family would offer bistecche to their Florentine citizens as a celebration in honour of San Lorenzo, on the patron saint's day, August 10. It is something that Tuscan families might have for birthdays or celebrating a holiday, something very special. So the offering of bistecca every day, all day, all over Florence for tourists is something that I think is incredibly unsustainable.

But there are ways that you could make it more sustainable.

I have a good friend whose family run an organic agriturismo called Poggio Alloro near San Gimignano that breed chianina cattle. They have an excellent restaurant where they serve their grilled bistecca only once a week, on Saturday nights. The rest of the week they offer other meats, dishes made with vegetables from the garden, their homemade cured salumi and local pecorino cheese. This makes sense. It is sustainable in many senses of the word. They have a bustling, busy restaurant where they feed 250 people a day in high season, but they still only offer bistecca once a week.

This is where I go to have bistecca. Not only because it's in a beautiful setting and I'm attracted to the fact that they are organic and family run, but also because choosing to eat their chianina is supporting biodiversity and the maintenance of this heirloom breed.

Chianina are an extremely ancient, large breed of cattle – one of the oldest in the world – that are native to Tuscany. As they are so large and muscular and are particularly adapt at pulling things and walking on unsteady, hilly terrain that they have long been used to help Tuscans farm. But once tractors and machinery became more mainstream, these heritage breed cows – which barely produce any milk, sometimes not even enough to feed their babies – could have gone into extinction.

Now Chianina cows are bred almost exclusively for meat, which has always been recognised for its high quality. It seems counterintuitive but in order to help heirloom animals survive, there needs to be someone to breed them, and a reason to breed them (and of course money needs to be made). It has a higher price tag than regular beef, but if we can eat much less meat we should be able to choose better quality meat, and that means quality not only in terms of flavour and nutrition but also in how they were raised — more naturally, more humanely.

Chianina are a breed that do not do well in intensive farm systems. So they come from small farms and this is something that makes them a more sustainable choice too. At my friend's agriturismo, where the cows are free, not tethered, and the calves stay with their free-roaming mothers until they are naturally weaned, they only keep a maximum of 50 animals.

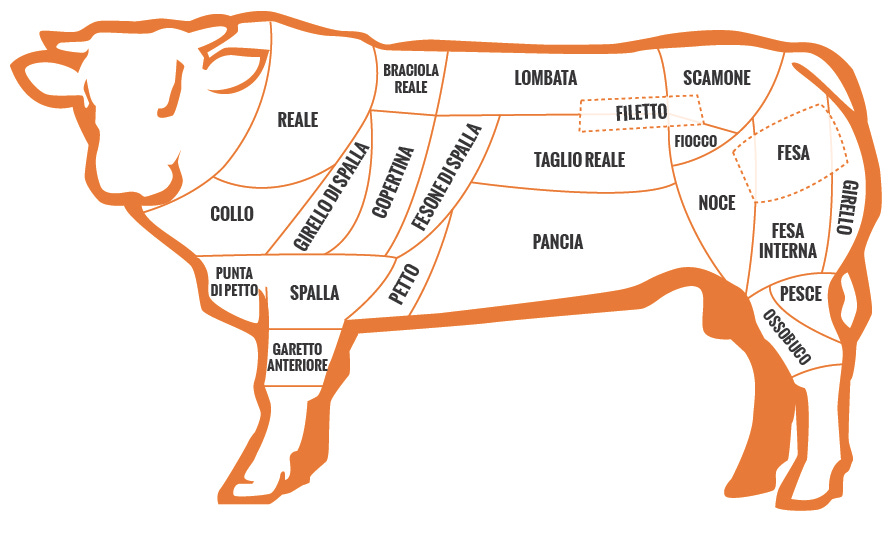

I also can’t help but think of the problem with offering only bistecca, of the fact that a cow is not only made of steaks. The cut used for bistecca comes from the lombata, or the loin, which is found near the animal’s spine (see above). My butcher friend Andrea Falaschi from his family's Slow Food butcher shop (and my local), Sergio Falaschi Macelleria in San Miniato, tells me that from the lombata you can get just 8, maybe 10, 1.5 kilogram steaks (a size for 2 people) from one animal. Look at the rest of it – there is a lot of meat leftover! And other than all the main cuts of meat you see here, what you don’t see on this ‘map’ of the cow, is the offal (also called quinto quarto in Italian, the “fifth quarter”), all the edible organs.

Abomasum or reed tripe is the last of the cow’s four stomachs and it is the least common in cooking. In fact, it is mainly the Florentines who seem to use it and still adore it today. While most tripe would be described as 'chewy' in texture, abomasum tripe or lampredotto is very soft and tender. It's delicious made into fried meatballs or stuffed into ravioli. Tripe is actually very delicate in flavour so it is often cooked or served with things that add big flavours to it. It's incredibly lean – leaner than a chicken breast – and very nutritious and very, very cheap. In a restaurant you're looking at 60 euro a kilo minimum for bistecca, and considering that an average bistecca for two people weights 1.2-1.5 kilos, you're looking at a much higher bill, around 90 euro, for that steak, while a very satisfying panino di lampredotto costs you just 4-5 euro.

Speaking as an omnivore, if we like to eat steak, I think we have a responsibility to eat also the rest of the animal too. Or at least try it – cook it, taste it, offer it. So much more has to be done to ensure that we are living sustainably. And I think that the Florentine restaurant scene – or at least the one aimed at tourists – is not sustainable, it is simply not future-forward at the moment.

More and more people are becoming aware that in order to help slow climate change, we need to make a change in our habits and the biggest, most effective change by far, it seems, is specifically to consume less beef.

Beef consumption has the greatest impact on resources and the environment, requiring more land (which also involves destroying carbon-storing forests to create pasture) and more water than other livestock or produce per unit of protein. They also emit large amounts of methane which contribute to green house gasses. In this graph you can see just how big an impact beef has compared to other legumes, meats and vegetables (the dark green line is pasture, the dark blue line is rainwater and the orange line is green house gas emissions). Imagine the effect of consuming and raising less beef.

In Creating a Sustainable Food Future, the World Research Institute found that if people who normally consume high amounts of meat and dairy shift to diets with more plant-based foods, even halve their intake of beef, then 5.5 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions would be avoided each year. And the UN says that cutting meat and dairy from our diet entirely would reduce our emissions by 66 per cent.

Many people seem to very aware of this now and already are mindful of what they eat. Already governments are aware that they will need to reach “peak meat,” that is, that livestock production needs to reach its peak and then decline continuously within the next decade (2030 is the goal) in order to tackle climate change. Experts believe that in some cases meat consumption is already at a point where it is declining, and even though this call needs large-scale change across western society, already, according to Guardian reports, “The fast growth of plant based alternatives to animal products could mean Europe and North America will reach 'peak meat' by 2025.”

Bruce Friedrich, of the Good Food Institute points out that “unless industrial meat consumption goes down, no government in the world will stand a chance of meeting their [climate] obligations.”

So this is something that I think restaurateurs really need to have the foresight to take into account as well. I’m not saying that restaurants shouldn’t serve bistecca, but perhaps a city as small as Florence doesn’t need so many steak restaurants. And if steak is on the menu, I would love to see more offal on offer too, and more of the fabulous legume and vegetable-forward dishes — dishes that are the backbone of Tuscan cucina povera. The change will come about with the request from consumers too, in particular from tourists, who are the main clients of these restaurants. If people are seeking out more vegetable based alternatives, or dining in places with more variety and choice of meat cuts, or at least care where the bistecca comes from (or how often it is offered), then hopefully restaurants could see this as an opportunity to become more sustainable rather than as a loss to the business.

The change won't come overnight but imagine having the opportunities to make more sustainable choices while eating out when traveling to a place like Florence, while still enjoying a new culture, exploring new tastes and of course having a wonderful dinner.

People say to me all the time, Tuscan food is so meaty, I'm really missing vegetables! All the time. This really gets me because Tuscan food is all about the vegetables (will talk more about this in another post — so much to say about the amazing vegetables here). Tuscan cuisine is inherently sustainable. It is based on cucina povera, where locally grown seasonal vegetables reign supreme. A no waste approach has always shaped Tuscan food and one thing that is done so well, so deliciously and cleverly, is the use of 'lesser' cuts of meat. I already mentioned earlier the lampredotto, but Tuscans eat absolutely everything. Kidneys, lungs, spleen, blood, heart, snouts, feet, tongue, even roosters combs, they’re all part of Tuscan cuisine — and wow, do Tuscans know how to make these taste so delicious, there is a lot to be learned here.

None of the animal is wasted in traditional Tuscan cuisine and this offal is integrated in the cuisine with the plethora of seasonal Tuscan vegetables (which I will get into on another post), smaller amounts of fish, other lean meat, cured meats, cheese, olive oil, wine and bread. This is a much more sustainable way to live and I believe — as an omnivore — that we should be raising less animals and eating less meat but also honouring the animal by being willing to eat all of it and not just the steaks. And if there is anyone who can make even the most unappealing parts incredibly delicious it is Tuscans, so there is a lot to be learned from these dishes.

Imagine if more restaurants adopted the historical culinary traditions of Tuscan, honouring seasonal vegetables, heirloom breeds and more attempts at proposing using the whole animal, not just the steaks.

I mentioned I’d tell you about my favourite question. One student asked at the end of this talk that he has some trouble getting past the “ick factor” of trying offal but that he was now really keen to try a panino al lampredotto and he asked if I had advice on how to get into it. I love this question, I love people being curious about food and trying something new — this is really the very first step. The second step is going with someone who is into it too! Take a friend who is more adventurous than you, who loves food, who can encourage you and maybe share with you if you don’t think you can stomach (pun intended) the whole thing.

The next step is to order the right thing. A panino al lampredotto is definitely the right thing! I love the ones they do at Tripperia Pollini near the Sant’Ambrogio church. I mentioned it’s a delicate meat. Order it with lashings of zingy salsa verde and if you like heat, plenty of chilli sauce. Order a small glass of red wine to wash it down with. Heaven! When I told my butcher friend Andrea Falaschi about this, he agreed and added his two cents — the dish to try for first timers, he said, is pulmone e patate, lungs and potatoes. He guaranteed that it would get you to love offal! Hard to find though, unless you have an old school nonna who will cook it for you.

There is also Il Magazzino, a “tripperia” restaurant in charming Piazza della Passera, specialising in offal and traditional Tuscan cuisine, that would be a fantastic place for a person curious to try offal for the first time. Their house antipasto has a collection of all kinds of things worth trying, including the best polpette di lampredotto — deep fried lampredotto balls. And this is another great way to get into offal, deep fried (as they say in Tuscany, fritta è buona anche una ciabatta — even a slipper is good deep fried)! The lampredotto ravioli are also divine.

Coming back to something I’ve been thinking about is what future there is for Florentine restaurants. There is a restaurant in Florence called Il Nugolo that I like to think of as representing “new” Florentine cuisine; it is the way I hope Florentine restaurants will continue progressing. The founder, Nerina Martinelli, is a young Florentine who spent many years living in London (she was at Petersham Gardens). Now that she is home, she takes inspiration from the kitchen garden she has set up in her family home, where she grows over 200 types of heirloom tomatoes to turn into produce-forward dishes. Beautifully presented dishes, freshest ingredients, such as oxtail-filled cappelletti with salsa verde and lemon zest, or spaghetti with fresh anchovies or a lip smacking dish of delicate, delicious animelle, sweetbreads, which are a very nice name for the pancreas. Nugolo was recently featured in Stanley Tucci's Searching for Italy show so I hope that this will also help put them on the map — I think this is the future of truly Florentine food.

As someone from the US, I definitely romanticized the European food system and pictured something more idyllic. So this was very interesting to me! Thank you for sharing.

Emiko, have you never been to Palermo? You will find that the panino di lampredotto is not in fact unique to Florence. Together with milza (spleen), it is THE street food of Palermo!